By: Lakeview Health

The Power of Craving: Why Do I Crave?

We are all vulnerable to addiction. “When we get hooked on the latest video game on our phone or our favorite flavor of Ben & Jerry’s ice cream, we are tapping into one of the most evolutionarily conserved learning processes currently known to science,” writes neuroscientist Judson Brewer in The Craving Mind. “This reward-based learning process basically goes like this: We see some food that looks good. Our brain says, Calories, survival! … See food. Eat food. Feel good. Repeat. Trigger, behavior, reward.” The feeling-good stage is primarily achieved by the release of the neurotransmitter dopamine. This mechanism is involved in all kinds of evolutionarily valuable behavior, such as sexual procreation. If repeated often enough such behaviors become automatic—they turn into unconscious habit loops. Unfortunately, this process not only helps humans repeat positive experiences; they frequently use it to numb negative emotions. Feel bad. Eat a sugary snack. Release dopamine. Feel better. Repeat. If you feel bad a lot, you will eat sugar-rich comfort foods way beyond any dietary requirements and endanger your well-being. Which will make you feel bad. Repeat.

The Role of Craving

Humans also learn to associate people, places, and things with the pleasurable feeling caused by dopamine surges. Through a process known as operant conditioning, the strength of any behavior can be modified by the behavior’s consequences. Drugs such as opioids and alcohol create unnaturally strong dopamine surges. If addiction develops, the brain craves the “remedy” every time it encounters a trigger. The sheer anticipation of using drugs or alcohol can now be triggered by external circumstances. “Addiction rides an evolutionary juggernaut: every abused drug hijacks the dopamine reward system,” writes Brewer. “Once behavior and reward are paired, the dopamine neurons change their phasic firing pattern to respond to stimuli that predict rewards. Enter the trigger into the scene of reward-based learning.”

The Addiction Cycle

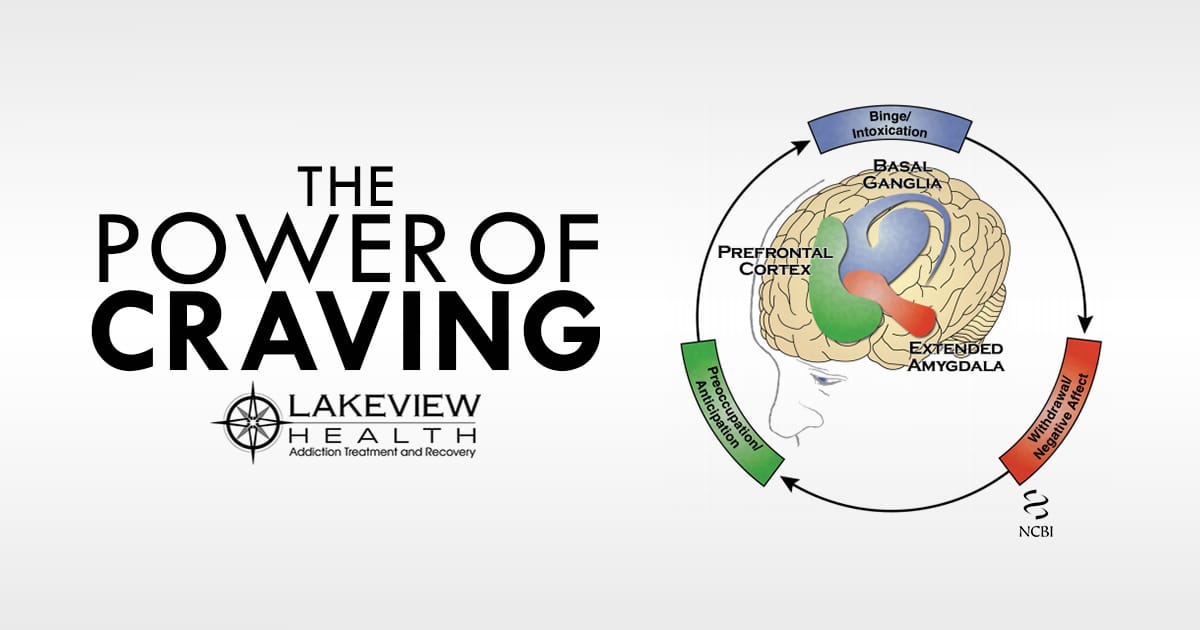

If addiction has developed and the substance is not forthcoming when triggered, withdrawal symptoms ensue. This can cause intense stress and physical pain, reinforcing the craving for release (negative reinforcement). In his comprehensive 2016 report on substance use disorders, Surgeon General Vivek H. Murthy described this cycle in detail.

Due to the phenomenon of tolerance, an addicted person has to take substances in ever higher doses. Since drugs and alcohol overstimulate the relevant receptors in the brain, it compensates by making more receptors available, resulting in the increased need to achieve the euphoria of the first high. This dangerous cycle is really a downward spiral of increasing craving and escalating substance use. Eventually, enormous doses are necessary just to feel normal. Once the habit loop is firmly established, it cannot easily be undone. This makes overcoming craving a central challenge in addiction treatment.

Post-Acute Withdrawal Syndrome

Long after patients’ medical detoxification, their acceptance that they are suffering from a chronic brain disease, and the beginning of their earnest effort to stay sober, cravings can resurface. For example, after the initial acute withdrawal symptoms during detox, patients often experience what’s known as post-acute withdrawal syndrome (PAWS). During this second stage of withdrawal, patients typically have fewer physical but more emotional and psychological withdrawal symptoms, including resurgent cravings. The most common PAWS symptoms are mood swings, anxiety, irritability, fatigue, low energy, difficulty concentrating, and disturbed sleep,” says Kacie Sasser, the senior director of medical services at Lakeview Health. Sometimes, the more severe symptoms of acute withdrawal return. This second wave of withdrawal symptoms often comes as a surprise to patients. “There are reported cases of PAWS symptoms up to a year into sobriety,” says Sasser. Cravings can unfold years after the end of active addiction, triggered by people, places, and things associated with the substance use. If patients walk past a bar where they used to get drunk many years before, they can suddenly be attacked by powerful cravings. Without appropriate coping skills, they might relapse. In The Power of Habit, Charles Duhigg suggests that habit loops once learned cannot be undone, only reprogrammed. That makes recovery a lifelong pursuit and addiction a complex disease requiring treatment on multiple levels over a considerable time span. The substance use disorder treatment program at Lakeview Health employs five levels of care to provide patients with the best possible toolset for a sustained recovery. In many cases, addiction and its concomitant cravings can only be checked by a comprehensive re-calibration of a person’s life. Recovery from addiction must be more than simply giving up substance use. “In residential treatment, we want to give patients a full body–mind–spirit experience,” says Dr. Philip Hemphill, the chief clinical officer of Lakeview Health. “The whole sense of self, the way they define themselves and function in society, is reset.”