By: Michael Rass

Most medical and addiction professionals now hold that addiction is a brain disease. In an influential article published 20 years ago, “Drug Addiction is a Brain Disease and it Matters,” Alan Leshner, then director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, proclaimed that addiction was a brain disease because “addiction is tied to changes in brain structure and function.” The term disease is frequently defined as “a condition of the living animal or plant body or of one of its parts that impairs normal functioning and is typically manifested by distinguishing signs and symptoms.” (Merriam-Webster) This can be fairly straightforward for an infectious disease. For instance, Ebola is a viral hemorrhagic fever of humans and other primates caused by a variety of viruses. Early symptoms include elevated body temperature, sore throat, muscular pain, and headaches. Vomiting, diarrhea, and rash usually follow, along with the decreased function of the liver and kidneys. So, Ebola is caused by an agent and impairs the functioning of vital organs, often causing the death of the infected person.

Diseases and Disorders

But what about behavioral conditions not caused by a virus or a bacterium? The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) serves as a universal authority for psychiatric diagnoses in the United States. It does not list diseases but disorders, including substance-related and addictive disorders. Mental disorders involve behavioral or mental patterns that may cause suffering or diminish the ability to function in life. Symptoms may be persistent, relapsing and remitting, or occur as a single episode. The causes of mental disorders are often unclear. Adrian Blotner, M.D., is one of the addiction specialists at Lakeview Health. He is board-certified in psychiatry and pain medicine. “Addiction is a disease because people who become addicted are biologically predisposed,” says Dr. Blotner. “Brain research shows that there are biological differences in the brains of people who become addicted compared to people who don’t become addicted.” “The DSM-5 categorizes mental conditions as ‘disorders’ because psychiatry focuses on observable behaviors,” explains Blotner. In the case of a disease such as diabetes mellitus, the focus is on a malfunctioning organ, the pancreas. To make the nomenclature even more confusing, some diseases such as diabetes can be described as a disorder. Also, what constitutes a disease or a disorder is debated among medical professionals, and opinions change over time. The American Medical Association (AMA) started classifying obesity as a disease as recently as 2013. Homosexuality, now considered a normal expression of human sexuality, was considered a mental illness not that long ago. In 1968, the DSM-II listed homosexuality as a mental disorder. In 1973, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) asked all members attending its convention to vote on whether they believed homosexuality to be a mental disorder. 5,854 psychiatrists voted to remove homosexuality from the DSM, while an astounding 3,810 still wanted to retain it.

Addiction as Moral Depravity

One of the earliest proponents of the disease model for addiction was Dr. Benjamin Rush in the 18th century. In his 1784 treatise An Inquiry into the Effects of Ardent Spirits, Dr. Rush referred to the “habitual use of ardent spirits” as an “odious disease.” Unfortunately, this Founding Father from Philadelphia was unable to convince other physicians of his understanding of addiction. Until the 19th century, alcohol misuse was mostly viewed as a moral iniquity. In colonial America, nobody understood alcohol and drug addiction the way we do now. According to Puritan minister Increase Mather, “Drink came from God but abuse of drink from the devil.” (Wo to Drunkards, 1673) “The Pilgrims and the Puritans, unlike most professionals today, saw the bad kind of drinking as a moral failure. As a result, the only recourse they had when faced with the destructive nature of drunken citizens was physical punishment. It didn’t work. They had no real treatment for alcoholism and no real understanding of what it was—they only knew that it was from the devil,” writes Susan Cheever in Drinking in America. Even when medical professionals began treating addiction as a disease, they had no concept of its etiology and no means to cure it. Numerous therapies were attempted in the “inebriate asylums” of the 19th century—none of them remotely evidence-based. It took the AMA—which was founded in 1847—until 1956 to recognize alcoholism as a disease. In the 19th century, the United States also experienced its first opiate crisis when morphine—often in the form of laudanum—was popular as a treatment for everything from coughing to laziness. Women were prescribed laudanum for the relief of menstrual cramps and nurses fed the drug to infants. Addiction became widespread as the addictive properties of opiates were little understood. Morphine was even used to cure alcohol addiction. As Dr. J. R. Black explained in a paper entitled “Advantages of Substituting the Morphia Habit for the Incurably Alcoholic,” published in the Cincinnati Lancet-Clinic in 1889, morphine “is less inimical to a healthy life than alcohol.” Sigmund Freud and a number of American physicians recommended cocaine in the treatment of alcoholism and morphine addiction. Professor Freud’s new therapy method of psychoanalysis was also unable to cure addiction. The prominent banker Rowland Hazard placed himself in the care of famous psychoanalyst Carl Jung for his alcohol use disorder in 1926. Hazard relapsed, and when he returned to Dr. Jung he was told that there was nothing left that medical or psychiatric treatment could do for him and that a “spiritual awakening” was his only hope.

Alcoholics Anonymous

A new approach to treat addiction appeared in the 1930s. Bill Wilson, a co-founder of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), had unsuccessfully tried to achieve recovery from his alcoholism in several clinics. Then he experienced the spiritual awakening that would launch his recovery and lead to the founding of Alcoholics Anonymous with Dr. Robert Smith in June 1935. Although the group refers to alcoholism as a sickness and a disease, its methods to overcome it are non-medical. But they were more successful than the “scientific” Gold Cure offered by the Keeley Institute. AA’s 12-Step methods have been adapted to address a wide range of substance abuse and dependency problems. More than 200 self-help organizations—often known as fellowships—with a worldwide membership of millions now employ 12-step principles for recovery.

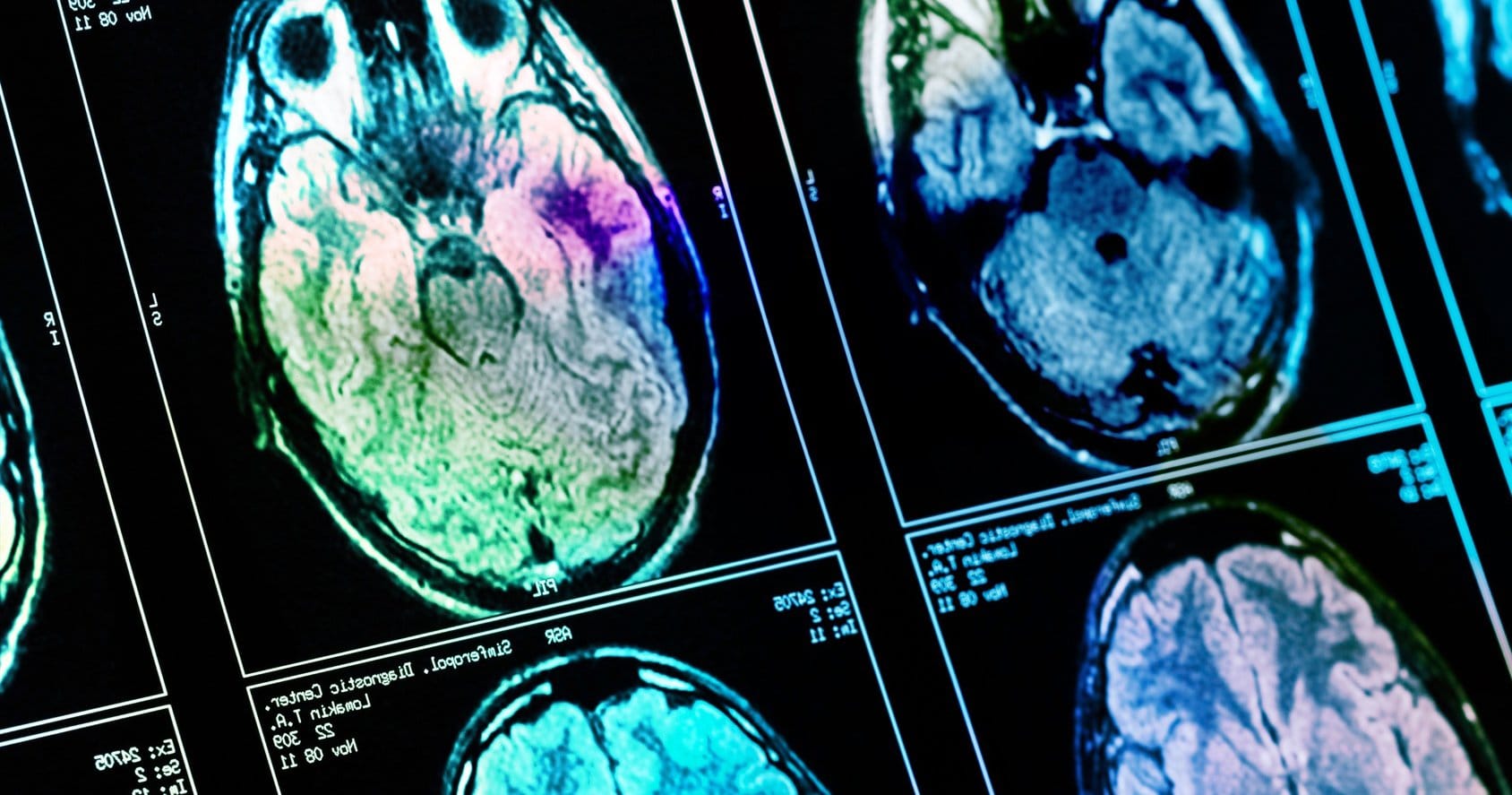

Chronic Brain Disease

Today, addiction is regarded as a disease by most medical professionals and their respective associations, including the American Medical Association. For the American Psychiatric Association, it is a complex condition, “a brain disease that is manifested by compulsive substance use despite harmful consequence.” The American Society of Addiction Medicine defines addiction as a primary, chronic disease of brain reward, motivation, memory, and related circuitry. “Dysfunction in these circuits leads to characteristic biological, psychological, social, and spiritual manifestations. This is reflected in an individual pathologically pursuing reward and/or relief by substance use and other behaviors.” In his comprehensive 2016 report on addiction, former Surgeon General Vivek Murthy “describes the neurobiological framework underlying substance use and why some people transition from using or misusing alcohol or drugs to a substance use disorder—including its most severe form, addiction.” Dr. Murthy’s approach is based on a modern scientific understanding of substance use disorders. “Well-supported scientific evidence shows that addiction to alcohol or drugs is a chronic brain disease that has the potential for recurrence and recovery.” While calling addiction a medical illness to be treated by “adopting an evidence-based public health approach,” Dr. Murthy also acknowledges the importance of fellowships like AA. “Mutual aid groups and newly emerging recovery support programs and organizations are a key part of the system of continuing care for substance use disorders in the United States.”

Learning Disorder

Some addiction experts distance themselves from the disease label, though. Journalist Maia Szalavitz has covered addiction topics for decades and has come to the conclusion that addiction is a learning disorder rather than a disease. In her 2016 book, Unbroken Brain, Szalavitz describes addiction in terms of a “coping style that becomes maladaptive when the behavior persists despite ongoing negative consequences.” “This persistence occurs because ‘overlearning’ or reduced brain plasticity makes the behavior extremely resistant to change,” plasticity being the brain’s ability to learn from experience. Several other authors come to similar conclusions. “There is certainly a failure to learn from experience among people with addiction,” says Dr. Blotner. “Those who do learn from experience go into recovery.” But addiction can certainly sneak up on you. “Some people walk around all their lives with a genetic predisposition. They might even be aware of it because of addiction in the family and stay away from addictive substances,” says Blotner. “Then they develop a pain condition and the doctor prescribes opioid pain relievers.” Just being exposed to addictive substances may now be enough to unleash overwhelming craving for relief leading to active addiction in such an individual. In his book The Craving Mind, addiction psychiatrist Judson Brewer explores the central role craving plays in developing a variety of addictive behaviors. Dr. Brewer, too, views addiction as a maladaptive use of the reward-based learning process. In a basic sense, addiction is a form of B.F. Skinner’s operant conditioning in which the strength of a behavior is modified by the behavior’s consequences. “Addiction rides an evolutionary juggernaut: every abused drug hijacks the dopamine reward system,” writes Brewer. Marc Lewis, author of The Biology of Desire: Why Addiction is Not a Disease, argues that the disease label leads to fatalism and the thinking becomes “I have a disease – what can I do? If I can’t get better, it’s because I have a disease, not because of anything I’m doing wrong.” For Dr. Blotner, this is a false conclusion. He says the disease model does not imply patients aren’t responsible for their behavior. “In the 1950s, American sociologist Talcott Parsons developed the concept of the sick role. A sick person has the right to disengage from social and occupational activities. Most importantly, the patient is not to blame. It’s not your fault if you have diabetes,” explains Blotner. “However, the patient also has an obligation to seek treatment and get better. Parsons’ sick role does come with rights but also with responsibilities for the patient.” That means people suffering from the disease of addiction have a responsibility to seek treatment and take good care of themselves. Nobody has a license to be irresponsible. “Just look at drunk driving,” says Blotner. “You don’t get to say the car accident wasn’t my fault because I’m an alcoholic. Society will still hold you responsible for your actions. It might not be your fault that you have an alcohol use disorder, but you have to be responsible for your behavior. You have to take control of your behavior to the point that you don’t harm others.” When it comes to the disease model of addiction, diabetes is the best analogy for Dr. Blotner. “The first things you try are diet and exercise. For some patients, that is good enough to control their diabetes. They were genetically predisposed to get it, their lifestyle habits had an impact, and when they changed their lifestyle their diabetes went away. Other patients get more severe forms of diabetes, and dietary adjustments and exercise cannot achieve an improvement. If the doctor puts you on medication, does that mean you don’t have to take care of yourself? Eat anything you want to eat? Not manage your blood sugar? No, you’re expected to take an active role in managing your health.”

More Research and Access to Treatment Required

All of this illustrates how complex substance use disorders are. As Dr. Murthy pointed out in his report, “no single treatment is appropriate for everyone.” At the National ℞ Drug Abuse and Heroin Summit in Atlanta last year, President Barack Obama said that to fully understand and solve the issue of addiction and drug abuse, a fundamental change was needed in the understanding of addiction as a preventable disease from law enforcement to doctors to the public. And people with an addiction need access to comprehensive, evidence-based substance abuse treatment. The team at Lakeview Health looks at all the needs of patients, including any underlying medical or behavioral issues that might be important contributing factors to the substance use disorder. “At the end of the day, it’s not about how we categorize addiction but about what we can do to get people to make healthier decisions,” says Dr. Blotner. “It’s not the patient’s fault that they have this craving to use drugs and alcohol, but it is their responsibility to try something different when the substance use is having such a negative impact on their life and the lives of people who care about them.”